Selective breeding in fish – written by Anna Blair

According to Darwin’s theory of evolution, the most successful organisms will survive to thrive and pass their genes on to the next generation. While environmental factors are normally the major determinant of reproductive success, when we interfere with natural selection, the gene pool is altered, a process termed Human Induced Evolution.

Selective agents

We tend to act as selective agents when fishing because there is a natural tendency to think that ‘bigger is better’ and to place a high value on ‘PB’s’ for different species. Large trophy fish often end up on the scales – most fishing contests bear witness to that observation.

Removing a disproportionate number of fish with certain genes from a population means those genes are not passed on in the same proportion to future generations and the percentage of those fish in the total population will decline.

Size-selective harvesting or killing of larger fish means a shift to greater proportions of smaller fish in the population. These smaller sized fish pass on their genes, so the average size in the population is shifted towards the smaller end of the scale.

Fisheries-induced evolution has been happening for decades and it happens much faster than natural evolution. Archaeological evidence confirms that the average size of snapper was once much larger than it is today. The age, size and weight of snapper at maturity has declined over time with the most likely causes an increase in fishing pressure and advances in technology.

Shrinking populations

Fisheries-induced evolution poses a threat to the future state of fisheries, affecting yields, stock stability and recovery potential of populations. Size-selective harvesting may cause fish populations to reach maturity at a younger age and smaller size, at which the individuals have lower productivity.

Large female fish produce more eggs and larger males produce more sperm, so the number of offspring per head of population tends to be larger than with populations containing smaller sized fish. Larger males also tend to be preferred by females and have more reproductive success than smaller male fish.

Genetic diversity is critical for the health and success of a population because it is the raw material for evolution. Genetic traits are naturally selected for or against, based on fluctuations in environmental conditions. A reduction in genetic diversity results in decreased ability of individuals to adapt to changing conditions: fewer individuals will survive in the event of environmental change and population size decreases. The fish that do survive to produce offspring pass on similar genes, contributing to greater genetic uniformity.

The cycle repeats, making it more difficult for a species to return to the productivity and diversity it once enjoyed.

Not only does fisheries-induced evolution have a negative effect on the fish populations themselves, but it also has social and economic implications, such as decreased commercial fishing potential and a reduction in the contribution of recreational fishing to New Zealand’s economy.

Norway’s cod

An example of fisheries-induced evolution has been exhibited in the case of the Norwegian cod stock. Large fish are prized in Norway and fetch higher prices at fish markets. The cod stock has undergone multiple declines since the first quota was introduced in 1978, and since 1930 the average size and age of sexual maturity in cod has decreased significantly.

Doctoral research fellow Anne Maria Eikeset of the Centre for Ecological and Evolutionary Synthesis published findings that suggested evolutionary change, as a result of the boom in the commercial fishing industry, is the culprit. As large fish go for the highest price, their genes for large size, increased reproductive success and later sexual maturity have continuously been removed from the population.

The fact that changes are being made at the genetic level means fishing, both recreationally and commercially, is affecting species more than we have been aware of. While some populations may be able to recover in terms of biomass, it is unclear whether reversals in terms of genetic diversity are possible.

Research models produced by various groups indicate that several years of evolutionary recovery will be required to restore populations to their highly productive and diverse states for each subsequent year of exploitation at its current rate. This ‘Darwinian debt’ will need to be repaid by future generations that are already suffering from other effects of environmental neglect.

Fish for the future

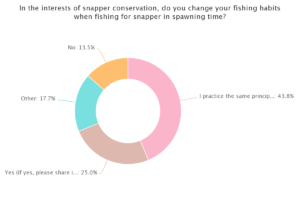

So, what can we do about it? Fortunately, there are a few ways we can aid the recovery of our great New Zealand fish populations and reduce the amount of genetic diversity lost through fishing. We already have a size limit on the lower end of the scale, so maybe an upper size limit could be introduced during breeding seasons to allow big fish to reproduce and pass on their genes.

So, what can we do about it? Fortunately, there are a few ways we can aid the recovery of our great New Zealand fish populations and reduce the amount of genetic diversity lost through fishing. We already have a size limit on the lower end of the scale, so maybe an upper size limit could be introduced during breeding seasons to allow big fish to reproduce and pass on their genes.

Releasing large fish will also be important and fortunately a change of attitude around killing the big ones is starting to filter through to most anglers.

Competitions should focus on sustainability rather than kill and weigh. Again, there’s a real shift to using measurement as the criteria for angling achievement. Today’s technology makes it easy to photograph a fish on a measure and have that recognised, but also allows big fish to be released to breed.

The DB Export NZ Fishing Competition is a good example of the use of technology to empower anglers to make their own decisions on what’s best for the fishery and sustainability.

We have an opportunity to make a positive change for future generations – letting some of those big catches go is worthwhile for the benefit of the future keen anglers of New Zealand.

So, when you tick off that bucket-list goal of a 20lb snapper or a 30kg kingfish, if it’s in good condition, maybe it can go back to keep those large-growth genes in the pool!

Anna Blair is studying genetics at Otago University.

This article is the property of NZ Fishing News and has been reproduced with their kind permission.

For more fishing related information, check out the NZ Fishing News website to subscribe for thier print or digital publications: NZ Fishing News

So, what can we do about it? Fortunately, there are a few ways we can aid the recovery of our great New Zealand fish populations and reduce the amount of genetic diversity lost through fishing. We already have a size limit on the lower end of the scale, so maybe an upper size limit could be introduced during breeding seasons to allow big fish to reproduce and pass on their genes.

So, what can we do about it? Fortunately, there are a few ways we can aid the recovery of our great New Zealand fish populations and reduce the amount of genetic diversity lost through fishing. We already have a size limit on the lower end of the scale, so maybe an upper size limit could be introduced during breeding seasons to allow big fish to reproduce and pass on their genes.